The controversy at Trinity University tells us so much about the loss of Christian conviction in colleges and universities, the insanity of secular revisionism, and the contradictions of Muslim students who are offended by the words “the year of our Lord,” but seem perfectly happy to have the name “Trinity University” printed in bold on their diplomas.

A group of students at Trinity University in San Antonio is petitioning the administration to remove the words “in the year of our Lord” from the school’s diplomas. Senior Sidra Qureshi said she started the petition in order to assure the school’s commitment to diversity. A Muslim student who presides over the “Trinity Diversity Connection,” Miss Qureshi told the media: “A diploma is a very personal item, and people want to proudly display it in their offices and homes. . . . By having the phrase ‘in the year of our Lord,’ it is directly referencing Jesus Christ, and not everyone believes in Jesus Christ.”

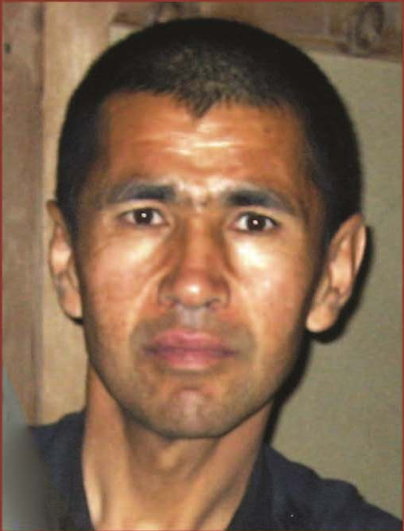

According to some accounts, the issue was first raised by Issac Medina, a convert to Islam who graduated in December of 2009. He told the San Antonio Express-News that he was offended by the language he found on his diploma, calling himself “a victim of a bait and switch” because he had been assured that the school no longer held to a Christian identity.

The school’s administration has sent mixed signals of its intention, but a decision by the university’s president and Board of Trustees is expected soon. Sharon Jones Schweitzer, assistant vice president for university communications told The Washington Times that the school will probably remove the phrase from all diplomas. The university’s president, Dennis Ahlburg, defended the wording as “unobtrusive.”

Many of the school’s alumni have protested the proposal, but momentum toward the change appears to be growing on the campus.

There are at least two significant dimensions of this controversy. The first has to do with what this reveals about the loss of Christian conviction and identity among so many church related schools. Trinity University was established in 1869 by Cumberland Presbyterians. The original faculty of five professors taught an inaugural class of seven students. Trustees first located the school in rural Tehuacana, Texas, hoping to put the students far away from the vices and temptations of larger cities.

The university’s published historical narrative explains: “Although religion played a prominent role in a Trinity education, the ethos was broadly Christian and no students were excluded because of religious affiliation.” In 1906 the school affiliated with the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America.

The decision to move the school to San Antonio came in 1941. In 1969, the school “modified” its relationship to the church by eliminating legal ties to the Presbyterian denomination. The new agreement between the school and the denomination “affirmed historical connections and pledged mutual support.”

This is the language of disengagement and secularization. Gary Luhr, executive director of the Association of Presbyterian Colleges and Universities, told The Washington Times that Trinity University is moving towards a relationship that is little more than a reference to the fact that the origins of the school “involved religion.”

As James Tunstead Burtchaell has documented and explained, “Countless colleges and universities in the history of the United States were founded under some sort of Christian patronage, but many which still survive do not claim any relationship with a church or denomination. Even on most of the campuses which are still listed by churches as their affiliates, there is usually some concern expressed today about how authentic or how enduring that tie really is; and often wistful thinking is all that remains.”

These schools have been effectively secularized, moving from identity as Christian colleges with clear Christian convictions, to church-related schools with ambiguous convictions, to schools with some historic tie to Christianity, but no Christian convictions at all. At this last stage, Christianity is more of an embarrassment than anything else. It seems that all parties related to the controversy at Trinity University are agreed that Christianity plays no official role in the life and work of the school in the present.

No one is claiming that the words “in the year of our Lord” mean anything theological in this context. The school holds to an essentially secular worldview — despite the language of the diploma, the Christian name of the school, and the image of the Bible on the school’s seal.

The second important dimension of the controversy is the insanity of thinking that the removal of the words “in the year of our Lord” will accomplish anything. Sidra Qureshi complains that the words are “directly referencing Jesus Christ, and not everyone believes in Jesus Christ.” Well, if those words offend anyone, how can they not be offended by the name of the university itself? Some have tried to explain the name in terms of the fact that the school had three predecessor institutions and was located in three Texas locations, but no one is denying the central fact that the word “Trinity” is a direct reference to the central Christian belief about God — and about Jesus Christ.

And what would the removal of the words “the year of our Lord” accomplish? That system of calendar dating can be traced back to Dionysius Exiguus, an abbot who in the year 525 constructed a new chart of Easter tables, changing the numbering of the years from the year one starting in 284, the year that Emperor Diocletian ascended to the throne, to what Dionysius calculated to be the year of Christ’s birth. Dionysius referred to the years after the birth of Christ as anni Domini nostri Jesu Christi (the years of our Lord Jesus Christ).

Thus, even when modern secularists try to change the language and dating customs from “A.D.” to “C.E.,” for “common era,” the date itself remains fixed with reference to the birth of Jesus Christ. Instead of “B.C.” for “before Christ,” these new agents of “tolerance” prefer “B.C.E.,” for “before common era.” But, once again, this does nothing to remove the fact that the number of the year points directly to the assumed date of the birth of Christ.

In other words, the only way to fully secularize the dating system is to renumber all the years with some other point of historical reference. Perhaps they would prefer we start with the year of Charles Darwin’s birth, then renumber the years as “B.C,” for “before Charles,” and “A.D.,” for “after Darwin.”

The controversy at Trinity University tells us so much about the loss of Christian conviction in colleges and universities, the insanity of secular revisionism, and the contradictions of Muslim students who are offended by the words “the year of our Lord,” but seem perfectly happy to have the name “Trinity University” printed in bold on their diplomas.

One thing is clear — the university will have to decide quickly what to do in this situation, and they will make their decision in — you guessed it — the year of our Lord, the two thousand and tenth.